Combating Climate Change: Opportunities for Directors and Boards

We are at a critical moment in human history. The pre COP 26 UN Climate Change Synthesis Report on Nationally Determined Contributions to achieving Paris Agreement targets suggested these will not be sufficient to contain global temperature rise to 2% above pre-industrial levels. Rather than bring the increase down to 1.5%, without further action the steps countries announced look set to result in global warming at catastrophic levels.

Recognising the Elephant in the Room

For some boards climate change is the elephant in the room they seek to avoid. For many others it is a threat and a source of increasing cost and risk. Further impacts of climate change will be felt around the world. In view of the number of people, places, corporate operations and aspects of life that are likely to be affected, for almost all businesses it could be both an existential challenge and an unprecedented opportunity.

The negative consequences of climate change are already with us and have been affecting a growing number of people over time. They range from excess deaths during peak temperatures to fires, floods, water shortages and droughts, crop failures and the inundation of low lying land. They are also increasing in frequency and severity. In the natural world, species and habitats are struggling to cope with the speed of change. Some are dying.

Scientific evidence suggests disasters and disruptions are likely to get worse, even if decisive action is now taken. Despite the dire projections, China, the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases with more than twice the emissions of the US in second place and four times the level of third placed India, is set to continue to build coal-fired domestic power stations. A laggard in reducing emissions, it only hopes to achieve net zero by 2060.

Taking the Initiative

Against this background and within boardrooms, some might argue it is already too late or that in the short-term stakeholders should not bear a disproportionate share of pain for the benefit of laggards. More responsible voices may argue there are many steps that we could all take that would buy time for sceptics to catch up, pressure on laggards to mount, laws and regulations to be introduced and a consensus to form in favour of more drastic action.

Around the world, individuals of all ages are taking the initiative. Innovators, problem solvers and entrepreneurs are adopting or devising practical steps that can be taken to address shared and inter-related existential challenges. There are affordable solutions with the potential to replace damaging activities and redundant jobs that could be quickly scaled up if supported by companies with relevant capabilities.

Within many boardrooms there are likewise opportunities for individual directors to step up and call for nettles to be grasped, reviews and changes of direction. They could and perhaps should speak up. Managements preoccupied with their own internal issues are sometimes oblivious to possibilities under their noses. The deadweight of some corporate overheads might quickly suffocate a new initiative, but other collaborations may be more fruitful.

Establishing Board Leadership

Boards have to determine what focus and priority to put on preparing for climate change and addressing it. Critically, they must decide how quickly to move, when short-term disruption and displeasure may have to be experienced to secure longer-term and collective benefits. As many other boards face similar pressures and dilemmas in relation to the speed of change, this could be a good time to consult widely among business partners and stakeholders.

Directors are not alone. They, boards and CEOs can also learn from their peers and share their experiences with others by joining one of the many networks that have been formed to help and support companies, whether local, national or international like the UN Global Compact and UNEP Climate and Clean Air Coalition. There are standards such as the IUCN Global Standard for Nature-based Solutions that a company could work towards.

Some boards, including those of family owned companies, might wish to review and refresh board membership. Should younger generations and those more likely to be affected by climate change be better represented on corporate boards? Given that they may have longer to endure the consequences of global warming, how otherwise might they be provided with more of a voice to ensure that their perspective has the weight it deserves?

Engaging and Initiating Critical Conversations

All members of staff, associates and supply chain partners could be asked to consider how they, and those they deal with, are likely to be affected by climate change and when. They could be asked for suggestions about what would help them to cope and what a company should do in response. Circular economy opportunities and possibilities such as recycling end of life products are often more productively explored collectively with like-minded interests.

Governance arrangements and expectations of directors might need to change to allow more time for strategic thinking and consideration of climate change issues. How informed are directors about the longer-term consequences of global warming? Are they thinking strategically of the implications of climate change between board meetings? What informal activities and exchanges might enable more climate related learning, thinking and discussion?

A board chair, helped by a deputy chair and/or senior independent director, might wish to talk individually to board members to get a feel for what they really think about climate change. A CEO could have similar conversations with members of a management team. Should such soundings be undertaken in confidence by an independent third party? Might people be more likely to open up if specific points are not attributed to particular individuals?

Reviewing Corporate Arrangements and Mechanisms

Mechanisms might be required to objectively and independently assess the extent to which board and management views on climate change are aligned, consistent and/or compatible. How do they compare with views held within stakeholder communities and among employees and business and supply chain partners? What are the similarities and differences? Do generations, business units and levels of management differ in their perspectives?

Should there be a climate change, transition or transformation committee that might enable interested non-executives to focus and discuss threats, opportunities and what needs to be done in more detail than is normally possible at board meetings? As with all committees, one would need to make sure its existence does not lead to the board as a whole avoiding its collective responsibility for areas covered by a committee’s remit.

Boards could consider how existing management mechanisms, practices and processes might be re-purposed. For example, key account management and key supplier reviews could be asked to consider how important customers and/or suppliers are likely to be affected by climate change and what could be done to help them and work with them, perhaps in co-creating more sustainable alternatives to current offerings.

Breaking Free from Current Attachments

There are various reviews that could be undertaken to identify both problem areas and potential opportunities. Delays in identifying problems may result in less time to address them and their eventual cost might be correspondingly higher. Being alerted and taking action earlier might save time and cost later. It could lead to a company being better placed to exploit areas of opportunity and possibilities for collaboration.

Some companies may end up paying a high price for trying to continue an existing business for as long as possible, while they are still able to do so. They might leave it too late to adapt or re-purpose capabilities and so face expensive write offs. They could also end up ill-equipped to cope with climate change in comparison with those that moved earlier while prices were lower and have since progressed along learning curves and built relationships.

Certain boards could consider whether traditional sources of advice meet current needs. Are their instincts and contributions rooted in the past? Have they been slow to suggest how to assess and address damaging activities? Some advisers and consultants may be part of ‘the problem’ rather than ideal partners on a different journey. A board might learn more from indigenous people about how to respect and co-exist in harmony with the natural world.

Reviewing Corporate Capabilities

Some boards rarely initiate reviews of corporate know-how or intellectual property (IP). Now could be a good time to assess what might be relevant for addressing climate change or coping with it. Is there IP that could be licensed to non-competing businesses or other bodies that might be able to use it and so generate additional revenue streams? Is there further know-how that could be accessed or acquired to complement existing IP?

Corporate capabilities acquired, developed and accumulated to enable and support past and current business activities may or may not be relevant as the consequences of climate change unfold. An assessment of likely or possible future capability requirements might reveal significant gaps and when they are likely to emerge. This could inform the timing of steps to change existing capabilities and acquire or develop new ones.

A review of corporate assets and infrastructure could also be undertaken to assess how these might be affected by climate change and when. Possible impacts could be physical, for example a risk of fire or flood, or financial, such as a loss of value or cost of repair or replacement. A resulting strategy could include back-up arrangements and plans for mitigation, contingencies and adaptation, or re-purposing or disposal.

Transition and Transformation Journeys

As global warming continues, different capability requirements may come and go at various points in the climate change journey. Some of these might therefore be temporary and contractual arrangements to provide cover may have to reflect how many other companies are or will be seeking similar capabilities. At local and national level, it may be possible to join a collective response. There might also be public body or Government initiatives to help.

Some companies may face daunting tasks such as winding down, ceasing operations and the responsible disposal of unwanted capabilities, followed by sale or liquidation. Boards need to be realistic. Much of what exists may relate to activities that are no longer desirable. Related capabilities might be better employed elsewhere. The scale of adjustment required across many economies is such that some people may consider specialist careers in this arena.

The innovation, education and promotion needed to switch demand and resources from damaging existing activities to more sustainable ones may give Schumpeter’s notion of ‘creative destruction’ new meaning. Imagination and drive may be needed to achieve a transition. Some directors may feel that thinking the unthinkable and winding up existing activities while others persist with them might give these competitors a sunset windfall.

Dealing with Climate Action Laggards

Internationally, the picture is not encouraging. At a macro level, there are significant variations in the dates by when different countries hope to achieve net zero, and the intentions of some laggards are questioned. Selfish countries might wish to secure most of the short-term gain of extra years of growth based on fossil fuel consumption, while incurring a smaller proportion of the consequential pain which will be borne by the whole global community.

A point may come when the laggards’ share of pain exceeds their gain. Before this is reached, within other countries responsible Governments and regulators may act to reign in those who continue to engage in damaging activities. At an international level, will one see responsible countries putting collective pressure on outlying laggards to desist from activities such as coal production? Will concerned publics boycott their companies’ offerings?

Some countries, such as totalitarian ones that are more self-sufficient economically, may resist diplomatic pressure and overseas public criticism. Given the conflicts that could arise over competing claims for diminishing water supplies or mass population movements, where they are able to do so, might activists or concerned states take steps to protect their interests, such as removing dams or closing down activities contributing to global warming.

Standing Strong against Pressures

We are entering an era in which it may be emotionally challenging as well as intellectually demanding to be a director. Those who are diffident or otherwise unwilling to rise to the challenge should consider stepping aside. Those who have spent years building something or on a certain course may not be the best people to now shut it down, release resources for more beneficial activities, create something new or move in a different direction.

Fossil fuel production is still sometimes subsidised. There may be pressures on businesses, including from some Governments to continue current activities for as long as possible, especially in developing countries seeking to ‘catch-up’. Endeavouring to match current consumption standards of more developed countries will eventually prove self-defeating, as both developed and developing nations need to move quickly to a more sustainable place.

Advocating and taking climate action may require courage and persistence. Survival within the finite limits of our planet requires the adoption of less materialistic and resource intensive lifestyles by communities and societies around the world. There are already unprecedented opportunities for creativity, innovation and business and social entrepreneurship, and many possibilities for pioneers to make their mark, scale up and maybe earn a place in history.

Revaluing Activities and Outputs

How we measure output and the make-up of GNP should be reviewed. It does not make sense for increases of damaging activities whose negative externalities are not accounted for to be simply included as additional output. Such externalities, and maybe exchanges within the barter economy and the voluntary work that people undertake to help and support each other, should be included in assessments of national output.

When negative and positive externalities, paid and voluntary work and barter exchanges are included, might switching from drawing down natural capital and destroying ecosystems to protecting, restoring and enhancing them result in an increase of wealth and wellbeing? Much could be done to re-wild, bring nature into cities and improve local environments. There are alternatives to being on treadmills and ramping up debt in order to accumulate and keep up

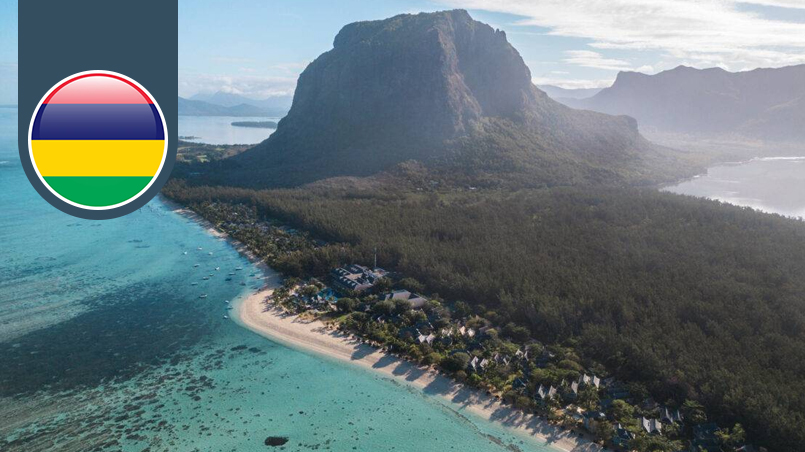

Could an attractive place be where more people live, rather than a holiday hotspot briefly visited by a few? Should periodic glimpses of a less pressured existence be replaced by more balanced lifestyles? Might a renaissance of local, arts and craft activities lead to a ‘good life’ that could be enjoyed by many people who hitherto have felt excluded? Addressing climate change could lead to a more inclusive, natural, healthier, satisfying and sustainable future.

Author

Prof Colin Coulson-Thomas

He holds a portfolio of leadership roles and is IOD India’s Director-General, UK and Europe. He has advised directors and boards in over 40 countries.

Owned by: Institute of Directors, India

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in the articles/ stories are the personal opinions of the author. IOD/ Editor is not responsible for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in those articles. The information, facts or opinions expressed in the articles/ speeches do not reflect the views of IOD/ Editor and IOD/ Editor does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.

Quick Links

Quick Links

Connect us

Connect us

Back to Home

Back to Home