Carbon Markets at a Crossroads

Will They Rise to the Challenge or Fade into Irrelevance?

Carbon is a boardroom variable affecting competitiveness, capital access, and corporate reputation.

Introduction

In the high-stakes climate chessboard, carbon markets were once seen as a masterstroke where emissions reductions could be bought, sold, and optimized globally. Yet, a decade into their evolution, questions remain: Can carbon markets deliver genuine climate outcomes, or are they merely an elaborate accounting exercise? As India prepares to formally operationalize its own carbon trading system, the global context, particularly the rules under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, matters more than ever.

Mandatory Carbon Markets: Rulebook vs. Reality

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement was designed to create a globally linked carbon marketplace. Specifically, Article 6.2 governs bilateral transfers of emission reductions known as Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes (ITMOs) while Article 6.4 envisages a centralized UN-supervised crediting mechanism, a successor to the CDM (Clean Development Mechanism).

As of mid-2025, only nine countries have submitted initial reports under Article 6.2-Switzerland, Ghana, Japan, Chile, Peru, Thailand, Senegal, the Dominican Republic, and Singapore, with Switzerland emerging as the most active ITMO buyer. Over 70 bilateral MoUs have been signed, yet actual trades remain sparse. The UNFCCC's latest dashboard shows just five ITMO transactions publicly disclosed, ranging between $20 to $45 per tonne, with volumes under 5 million credits globally underscoring the nascent liquidity of this compliance regime.

Turbulent Maturity

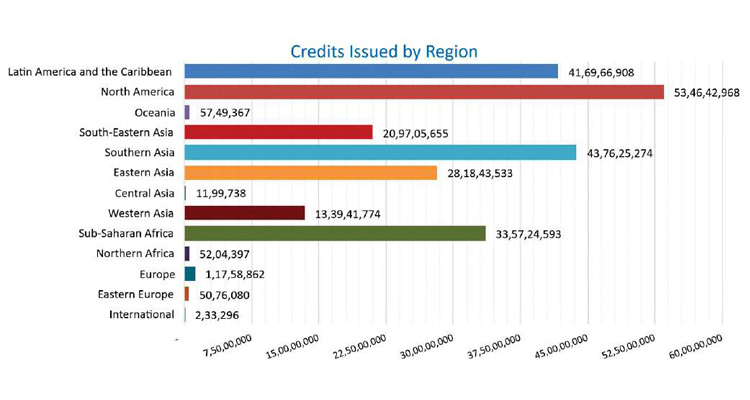

Globally, the Voluntary Carbon Market (VCM), long seen as the sandbox for innovation, is undergoing intense scrutiny. Prices, once surging post-COP26, have crashed due to quality concerns, NGO exposés, and shifting buyer preferences. The VCM's issued over 2.38 billion credits (as of April 2025), with 1.37 billion retired. India features prominently among VCM contributors, ranking in the top 3 globally. A large share of India's credits came from:

• 477 wind projects (~135.8 million credits issued)

• 154 solar projects (~101.4 million)

• 303 clean cook stove programs (~16.3 million)

These were largely purchased by foreign buyers, including Japanese firms, EU utilities, and U.S. tech companies. Despite its contributions, India's own domestic usage of these offsets remains negligible highlighting a disconnect between climate export and domestic climate strategy.

India's Carbon Market: Poised between Ambition and Ambiguity

India notified its Carbon Credit Trading Scheme (CCTS) in 2023 under the Energy Conservation Act, aiming to India, despite being an early architect of carbon projects under the CDM era, has not yet authorized any Article 6.2 transaction or submitted an initial report. India's domestic carbon trading framework, the Carbon Credit Trading Scheme (CCTS), has been formally notified under the Energy Conservation Act. While its architecture is being shaped under the Bureau of Energy Efficiency (BEE), the scheme has yet to be aligned with Article 6 protocols of the Paris Agreement.Voluntary Markets: A Story of replace the older PAT and REC mechanisms. The Draft Carbon Market Policy (March 2024) outlines a phased implementation with regulatory oversight from the BEE and MoEFCC, under a new entity called the Indian Carbon Market Governance Board (ICMGB).

The foundational elements, MRV protocols, sectoral baselines, credit authorization rules, and a national registry are in development. However, several blind spots remain:

• No clear buyer obligation: Unlike the EU ETS or China ETS, India's design does not yet mandate specific emissions caps.

• Unlinked with Article 6: While capable of generating domestic credits, the CCTS is not recognized under UNFCCC mechanisms.

• Governance overlap: Fragmented roles between MoEFCC, BEE, and ICMGB may delay execution.

India's past as a major carbon exporter via CDM projects gives it the capacity and experience, but the market must evolve from an export-led model to one that drives domestic decarbonization.

Box Story: India's Voluntary Carbon Surge

Between 2010 and 2024, India became one of the world's largest suppliers of voluntary carbon credits without a functioning carbon market of its own. Over 375 million credits were issued from Indian projects, with 215 million retired by global corporates seeking to meet climate targets.

From wind farms in Gujarat to solar parks in Rajasthan and clean cook stoves in rural heartlands, India delivered scale, speed, and certification - under global standards like Verra and Gold Standard. Yet, these credits served foreign ESG strategies far more than India's own.

What emerged was a carbon services economy: project developers fluent in international protocols, driving climate gains abroad while India's domestic emissions challenge remained largely untouched.

As global markets move toward Article 6 compliance and sovereign registries, India must now ask - will it remain the world's carbon offset supplier, or build a market that serves its own net-zero path?

Comparison Box: How India Compares (as of April 2025)

| Metric | Global Total | India's Share | % of Global Total |

| Credits Issued | 2.38 billion | ~375 million | ~15.7% |

| Credits Retired | 1.37 billion | ~215 million | ~15.7% |

| Active Projects (VCM) | ~10,364 | ~1,170 | ~11.3% |

What Makes a Carbon Market Work?

Credible carbon markets such as the EU ETS, Korea ETS, and China's national system are anchored by five critical pillars:

1. Legally binding emission caps or compliance obligations

2. Robust Measurement, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) protocols

3. Transparent, tamper-proof digital registries

4. Enforceable penalties and independent audit mechanisms

5. Strong public-private engagement and cross-sector participation

Boards and CXOs must now shift carbon from a citation in an ESG report to the strategic roadmap.

India's proposed Carbon Credit Trading Scheme (CCTS) addresses foundational elements such as MRV and registry design. However, it still lacks:

• Clarity on enforceable compliance obligations (no defined emission caps or buyer mandates)

• Codified penalty structures and third-party audit governance

• Sector-specific incentives to ensure broad-based participation

Without these essential mechanisms, India risks creating a procedural market rather than a functioning price-based decarbonization instrument.

Boardrooms and Carbon: What Directors Must Watch

India's transition from a carbon exporter to a compliance driven market presents both a governance imperative and a first-mover opportunity. Boards and CXOs must now shift carbon from a citation in an ESG report to the strategic roadmap.

What should directors watch?

• Scope 3 exposure: Indian exporters to the EU are already impacted by the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). Tata Steel, for example, has begun integrating low-carbon processes and emission disclosures to safeguard its market access.

• Supply chain preparedness: Are your Tier 2 and Tier 3 suppliers ready for allowance-based trading? Without upstream integration, large corporates risk carrying the carbon burden of their value chains.

• Offset credibility: Using low-integrity credits can undermine ESG claims and invite investor or regulator backlash. The bar for climate transparency is rising.

• Timing capital investment: Early movers into energy transition technologies i.e., green hydrogen, biomass, carbon capture, may benefit from preferential access to sectoral carbon credits in Phase 1 of India's trading scheme.

This is no longer a CSR conversation. Carbon is a boardroom variable affecting competitiveness, capital access, and corporate reputation.

Conclusion: Will Carbon Markets Rise or Fade in India?

India's carbon market sits at a three-way fork:

• Rise: If binding compliance obligations are introduced, Article 6 linkage is achieved, and digital infrastructure is robustly deployed.

• Stumble: If governance remains fragmented and participation is limited to a few dominant corporates.

• Fade: If carbon prices remain weak, credit integrity is questioned, and private demand stagnates.

India has the regulatory will, project capacity, and market momentum. What it now needs is boardroom conviction.

For Indian directors and institutional investors, the next 24 months will define whether carbon markets become a cornerstone of national climate competitiveness or another well-intentioned policy that failed to take root.

Author

Ms. Chandni Khosla

She is an Independent Director, ESG and Sustainable Finance expert with over 25 years of experience in capital markets across Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. She has served in senior roles at Singapore Exchange, NSE India, HDFC Limited, and Natixis Investment Managers. She advises companies, regulators, and boards on ESG strategy, Sustainable finance. Chandni is a Fellow of the Institute of Directors, Senior Executive Fellow of Harvard Kennedy School and regularly contributes to global forums on sustainability transitions.

Owned by: Institute of Directors, India

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in the articles/ stories are the personal opinions of the author. IOD/ Editor is not responsible for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in those articles. The information, facts or opinions expressed in the articles/ speeches do not reflect the views of IOD/ Editor and IOD/ Editor does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.

Quick Links

Quick Links

Connect us

Connect us

Back to Home

Back to Home